Feel free to add tags, names, dates or anything you are looking for

Nikoloz Kandelaki is one of the most outstanding representatives of modern Georgian art, and the development of realistic sculpture in Georgia is associated with both he and Iakob Nikoladze. In addition to his creative genius, Kandelaki was a brilliant educator. He founded the Kandelaki School, where numerous gifted Georgian sculptors honed their craft. His impact on Georgian sculpture was deep and enduring. Born in the village of Kulashi in 1889, Kandelaki attended school in Kutaisi, moving on to pursue his studies at the Leningrad (St.Petersburg) Psycho-Neurological Institute. His medical education provoked his interest in the structure of plants and the human body. He displayed his skills while creating sculptures. During that time, Kandelaki created a wax portrait of Plemanikov, which received much acclaim when it was put on display. Encouraged by this success, he was advised to enroll at the Leningrad Academy of Arts. Before joining the Academy, Kandelaki perfected his skills in the workshop of L. Dimitriev-Kavkazsky on the advice of his classmate and renowned artist, David Kakabadze.

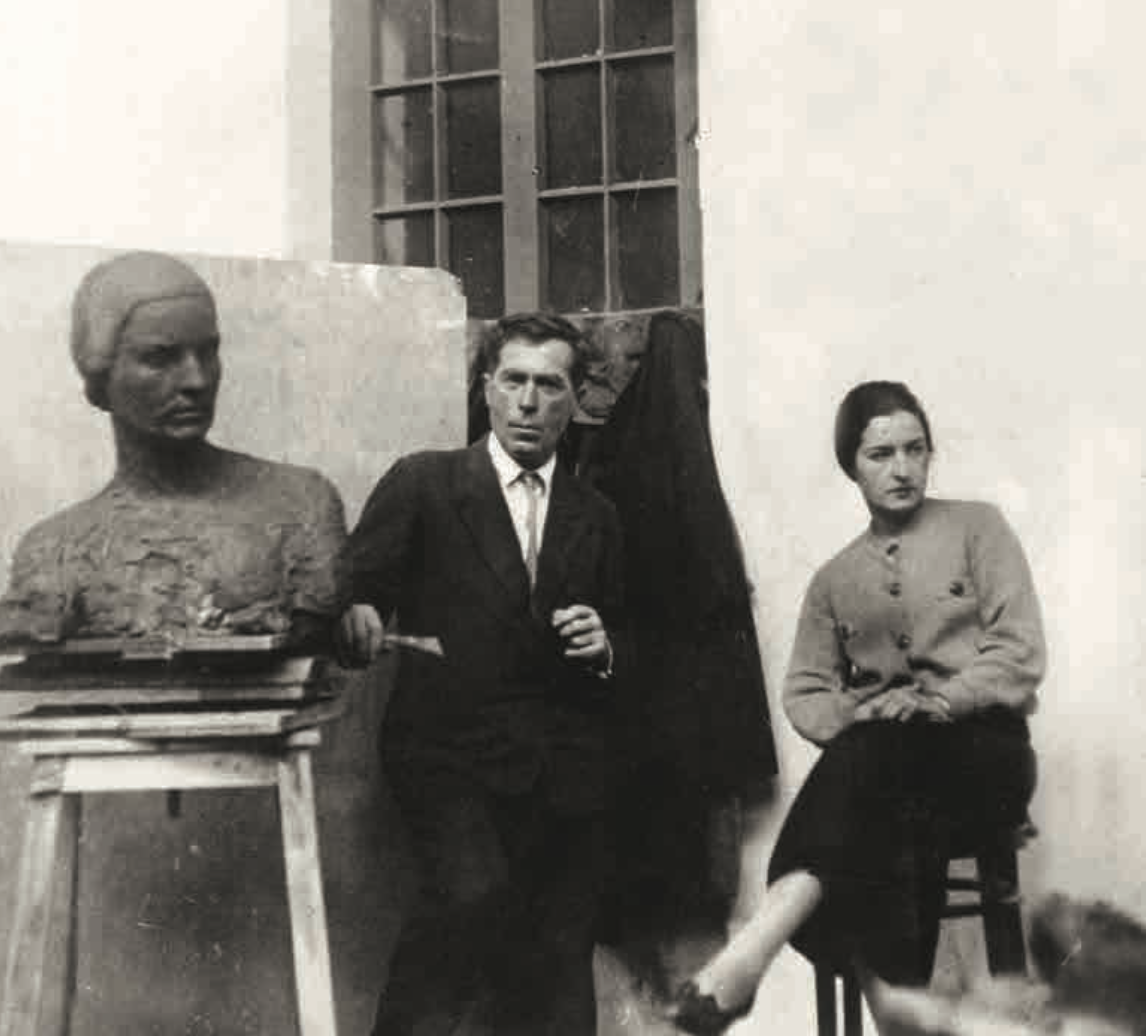

Nikoloz Kandelaki (1889-1970) in the Sculpture Studio of the Academy of Arts, 1955

Nikoloz Kandelaki (1889-1970) in the class of L.Dimitriev-Kavkazski. In the shot, N. Kandelaki is seen from behind, while painting a naked figure. St. Petersburg, 1910

Georgian Artist; Standing: The first from the left D.Kakabadze, N.Kandelaki, K.Kaladze, L.Gudiashvili, Sitting: the first from the left K.Zdanevch, T.Abakelia, D.Arsenishvili. The first half of the 1930s

Nikoloz Kandelaki was admitted to the Academy of Fine Arts in the class of A. Matveev, and, indeed, the influence of this teacher runs through all of Kandelaki's work. Matveev demanded loyalty to the models and a thorough understanding of their possibilities. The fullness of sculptural form, materiality, and the clear structure of construction are just a partial list of what Kandelaki firmly absorbed during his studies at the Academy of Fine Arts. His diploma work, though not preserved, earned him widespread admiration and a state scholarship for further studies abroad. Yet Kandelaki chose to stay true to Georgia, returning to his homeland in 1926. Upon his return, Kandelaki immersed himself in Georgia’s cultural life. He quickly established himself as a master portraitist, a genre that became central to his artistic identity. His portraits captured the essence of his contemporaries—both prominent figures and ordinary working people.

Nikoloz Kandelaki (1889-1970) while sculpting the figure of N. Dumbadze, 1950s

In the sculpture studio: on the right N. Kandelaki, on the left I. Nikoladze, Georgian Academy of Arts, 1926

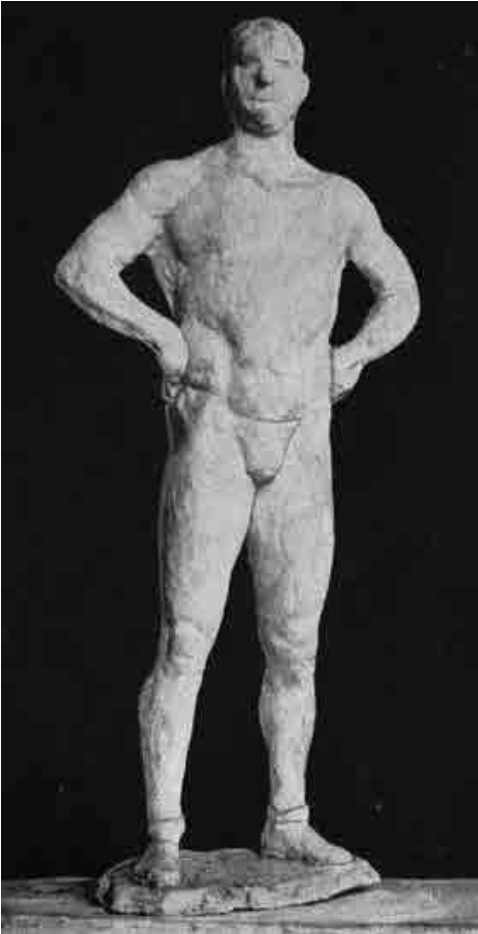

Kandelaki’s portraits are marked by their strong construction and emotional intensity. The axial contrasts in his sculptures enhance dynamic movement and create a sense of tension, while the sharp outlines and rough sculpting style convey unyielding precision. His works reflect heroism, masculine strength, and perseverance—qualities inseparable from Kandelaki himself. Described as a towering figure with stern features and a mane of light-colored hair, Kandelaki’s imposing presence mirrored the character of his sculptures.

Nikoloz Kandelaki (1889-1970). “Athlete. Weightlifter”. Fragment

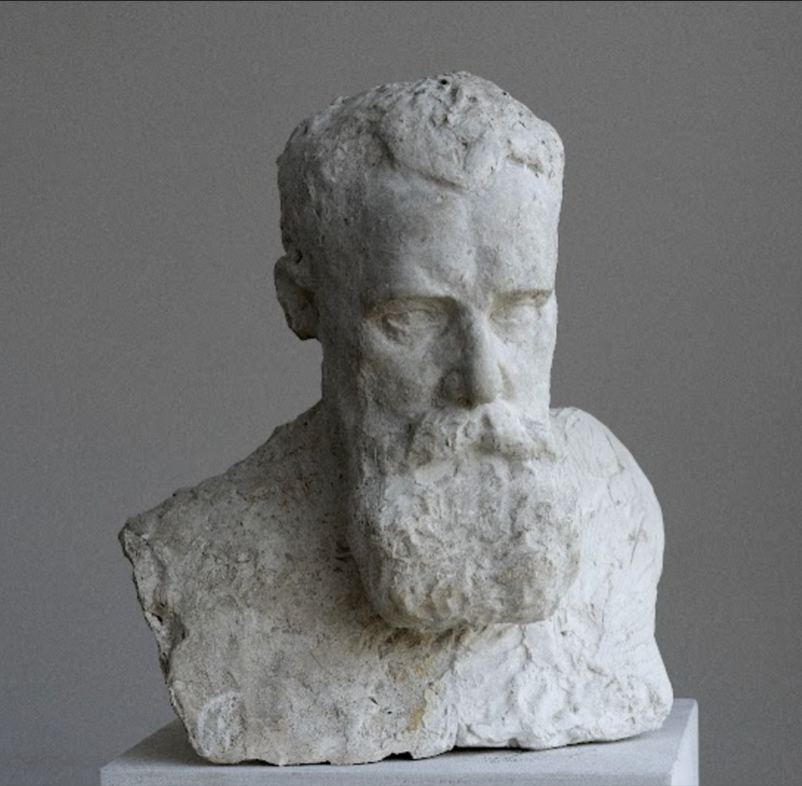

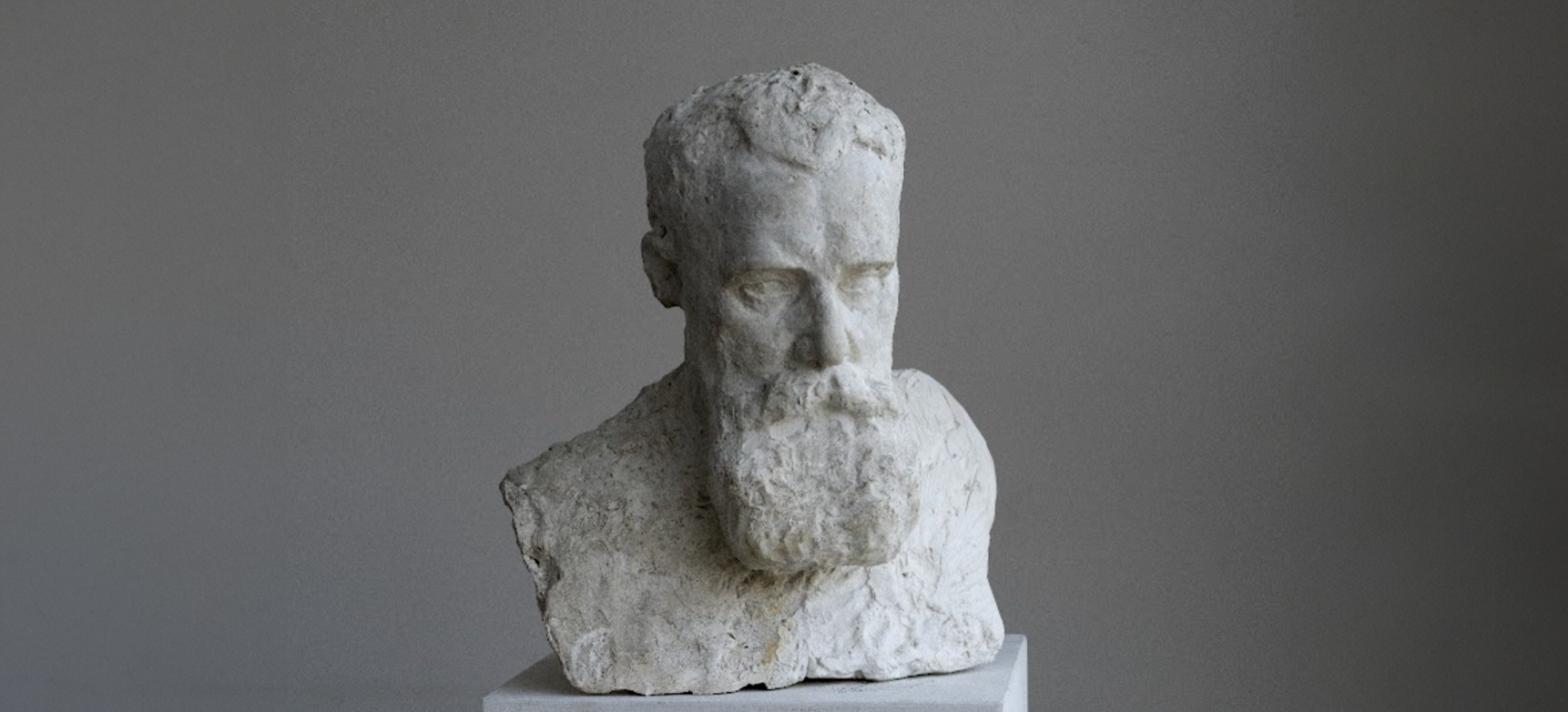

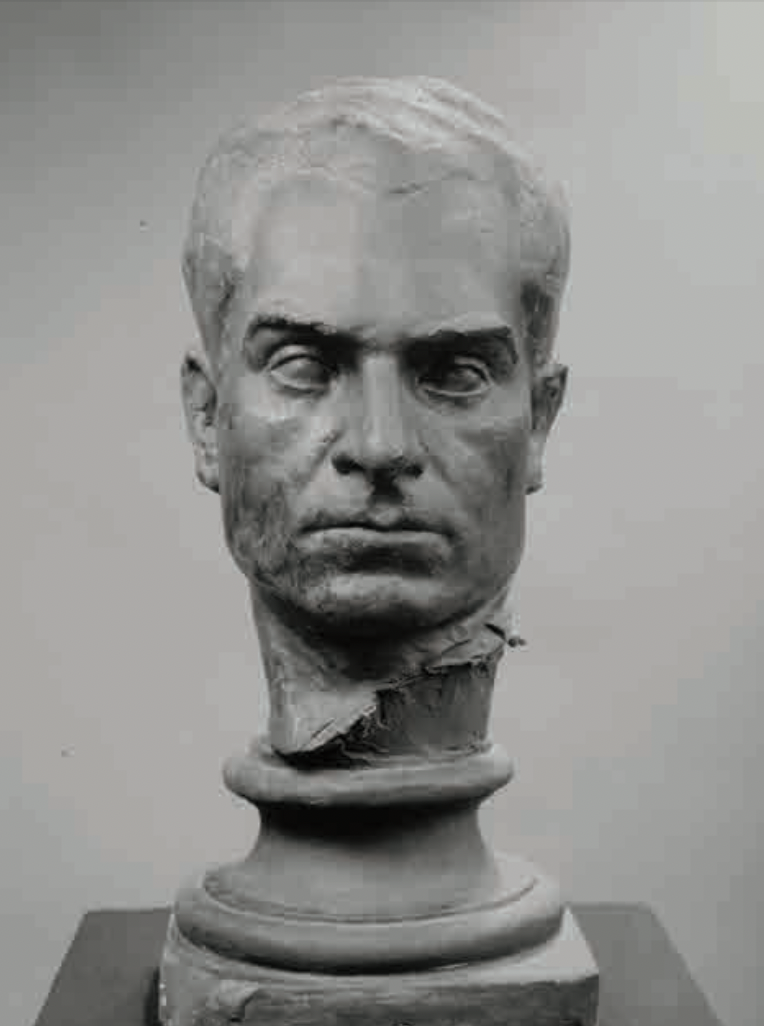

Nikoloz Kandelaki (1889-1970). “Portrait of an unknown man”, Plemyanikov. 12x11x5. Tinted plaster. 1921. Private collection.

Kandelaki was known for his uncompromising and critical approach toward government, societal norms, and educational practices. No one ever saw him bow his head. His authority was universally respected, and his peers admired him. Generations of Georgian sculptors remain grateful to Kandelaki for encouraging their individuality and fostering their growth as artists. From 1929 until his death in 1970, Kandelaki headed the Department of Monumental Sculpture at the Tbilisi Academy of Fine Arts. His leadership and mentorship left an indelible mark on Georgian art. Monumentalism is the distinctive feature that invariably accompanies all the works of Nikoloz Kandelaki. His sculptures were characterized by clear, pronounced plastic forms and a harmonious unity of silhouette, making them impactful even from a distance. Each composition encourages viewers to observe the work from multiple angles, revealing new emotional and structural nuances.

Nikoloz Kandelaki (1889-1970). Facade plastic art. Foreshortening

Nikoloz Kandelaki (1889-1970). “Village scene”. 3x1.70m. Bas-relief. Plaster. 1929

Each new viewpoint allows us to gain a deeper understanding of the diversity of the sculptures' external and internal emotions. The works ‘Miner from Imereti’ (1938), ‘Akaki Khorava’ (1935), ‘Lado Gudiashvili’ (1933–1935), amongst others, are notable in this regard. Kandelaki's primary creations were portrait busts, each set on a basic pedestal - round, profiled supports that were designed solely to enhance the look of the face. Kandelaki exhibited the same level of expertise in the creation of sculptures carved from stone as he didas those made of clay and later bronze.

Nikoloz Kandelaki (1889-1970). “Kolkhi - Imereli miner”.48x42x28 cm. Tinted plaster. 1938. Sculptor’s studio

Nikoloz Kandelaki (1889-1970). “Portrait of the Hero of Labour, miner” K. Iluridze. 54,5x62,5x33,5 cm. Tinted plaster. 1957. GNM. National Gallery of Pictures

Nikoloz Kandelaki (1889-1970). “Akaki Khorava”. 385x103x41cm. Stone. 1979. Arch. Vakhtang Davitaia, Senaki. In front of the State Drama Theater of Akaki Khorava.

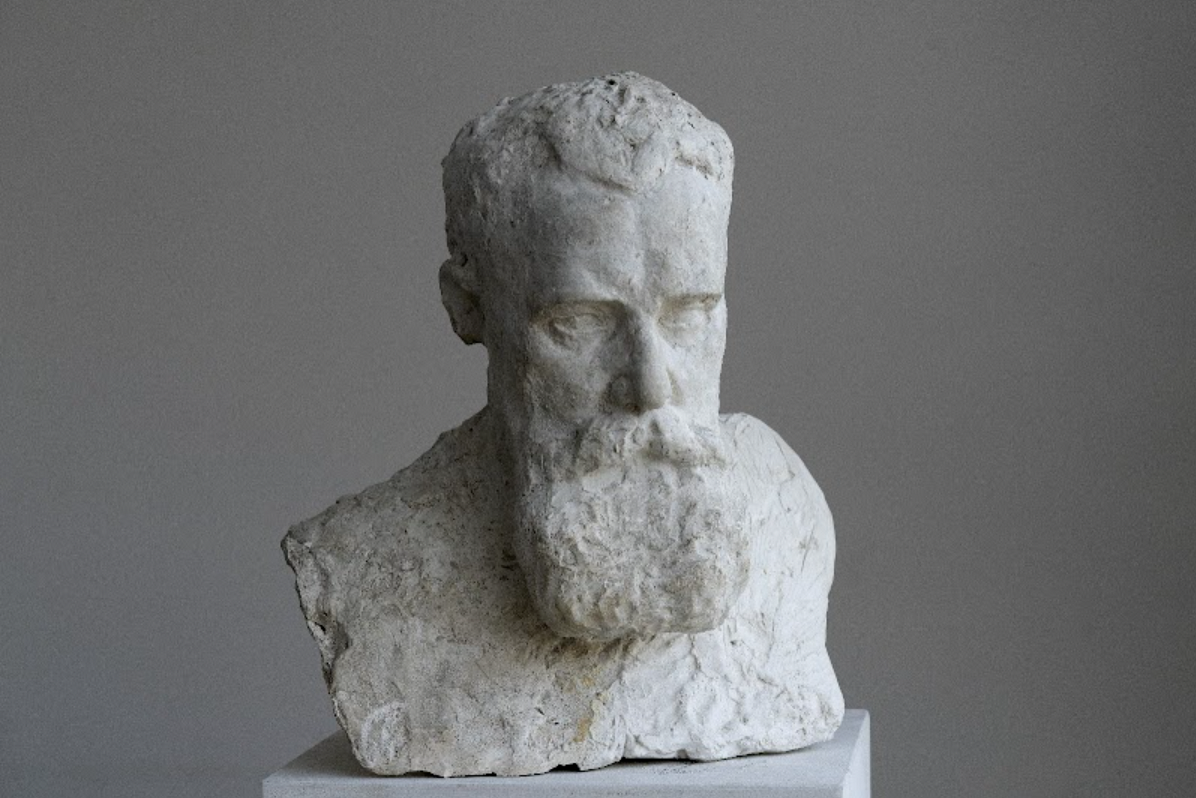

His portrait of Lado Gudiashvili (1933) is particularly noteworthy. The sculptor not only achieved a striking resemblance to the model, but also accurately caught the expressiveness of the facial features. These features include a high forehead, an eagle-like gaze, sharply outlined lips, high eyebrows, and a heavy jawline, imbuing the sitter with the qualities of an indomitable individual. At the neck, the statue is cut obliquely, creating the illusion of an abrupt head-turn. The plastic forms are sculpted with a precise, skilled hand, and their mutual harmony is readily apparent. Two years on from this work, Kandelaki sculpted a portrait of the same subject in stone. He altered the composition, presenting Lado Gudiashvili in a bust, cut beneath the breast. The stone block is crudely shaped below the chest, enhancing the sculpture's plasticity and expressiveness. In contrast to the bronze version, the character of the portrait is further accentuated by the material. A strong axial contrast is the foundation of the motion. The rightward tilt of the head and the leftward tilt of the shoulders characterize this posture. The result is a spatially expanded movement that compels the observer to survey the monument from every angle. The sculpture seems to be locked in space by an invisible, tight form - no matter which angle you look at it from.

Nikoloz Kandelaki (1889-1970). “Portrait of Lado Gudiashvili”. 65x60x30 cm. Stone. 1936. GNM. Georgian State Museum of Arts

Nikoloz Kandelaki (1889-1970). “Portrait of Lado Gudiashvili”. 50x40x25 cm. Tinted plaster. 1934. Sculptor’s studio

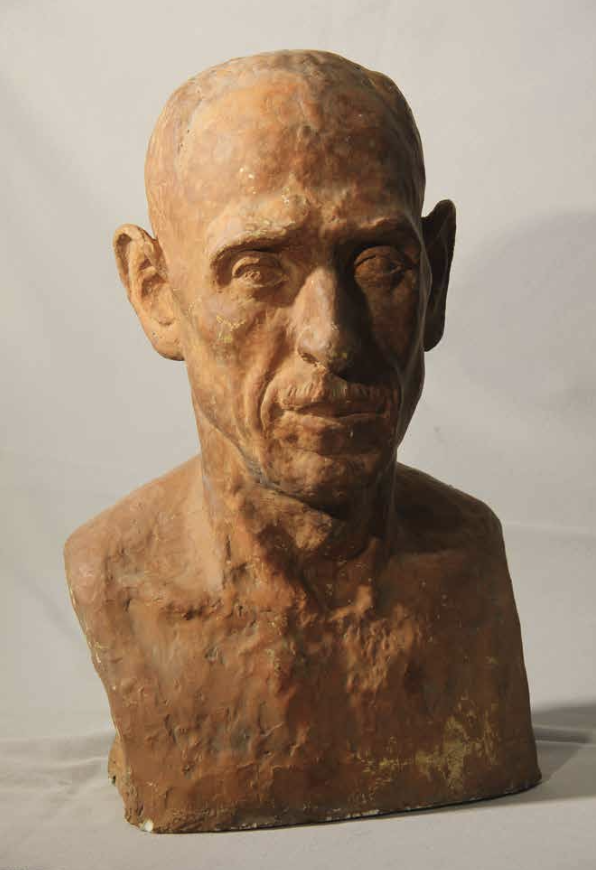

More than one portrait has survived where Nikoloz Kandelaki uses an etude artistic manner, and the artist’s trembling hand can be seen behind the work. His student, M. Berdzenishvili, recalls that he sculpted the model with such emotion and passion, that his students, who witnessed it, were greatly impressed. Kandelaki’s traditional multiple sessions sometimes ended with just a few glances having been gained. Such is the portrait of Galaktion Tabidze (1957). Kandelaki understood well that it would be impossible to get the always bustling Galaktioni to sit as a model for long. The sculptor seemed to be in a hurry to translate his emotions into plastic language. Can anyone forget Galaktioni's manner of reading poetry? His quick, exciting storytelling? Galaktion’s voice appeared to surge like a torrent, threatening to overrun everything. This is exactly how Kandelaki sculpted, as if he was rushing to capture the poet’s deep thoughts and terrible sorrow. The sculpting technique is quick, and possesses the life-giving distinctiveness associated with impressionism. The boundaries of plastic forms are blurred as they flow into one another. The sculptor created a romantic, inspired face for Galaktion Tabidze, giving us a sense of the flow of time and its transience.

Nikoloz Kandelaki (1889-1970). “Portrait of Galaktion Tabidze”. 54x57x33,5cm. Plaster. 1957. ATINATI Private Collection

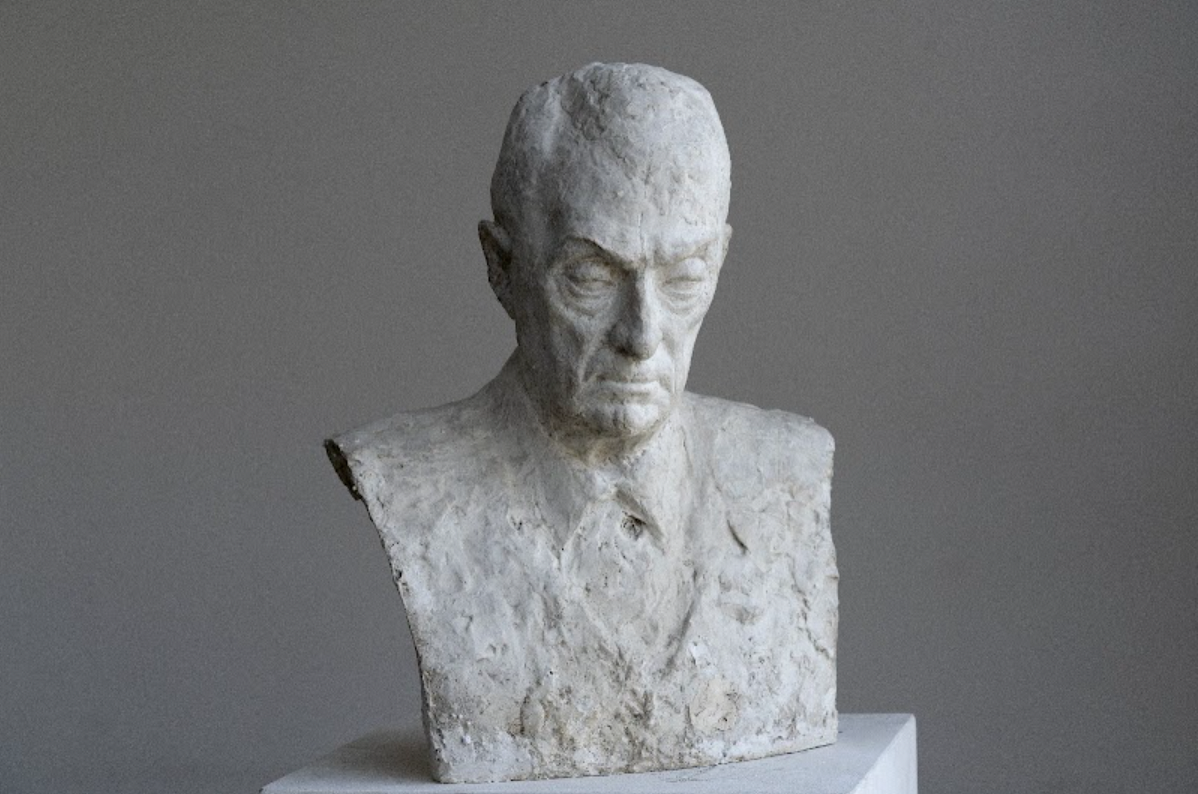

The bust is equally impressive of Konstantine Gamsakhurdia (1969), sculpted at the end of Kandelaki’s life. Gamsakhurdia had a uniquely impressive face: with a raised brow and tightly pursed lips, he resembled a Georgian knight. Kandelaki showed Gamsakhurdia in a frontal position. Only a small inclination of the head and the downward gaze of his large eyes convey the writer’s image as a person immersed within himself. The portrait was sculpted using a delicate, free-form approach. Nothing is exaggerated in it, but that tilt of the head emphasizes the importance of the forehead, indicating the writer’s intellectual work. The sculpture of Konstantine Gamsakhurdia has incredible inner vitality, demonstrating the sculptor’s exceptional technique.

Nikoloz Kandelaki (1889-1970). “Portrait of Konstantine Gamsakhurdia”. 54x43x24cm. Plaster. 1969. ATINATI Private Collection

In the history of Georgian sculpture, Kandelaki's portraits played a very important role, as they determined both the overall style of subsequent Georgian sculpture and the main line of the author's portraiture. Nikoloz Kandelaki's portraits of men are nearly always decorated with heroic traits, although he also enjoyed portraying romantic, sensitive characters. In this sense, the portrait of art researcher Academician Vakhtang Beridze is notable, seeing the sculptor creating the face of an inspired man. The sculpting style is gentle, and the plastic shapes are almost flexible. In Kandelaki's portrait collection, we can also see women's faces. While their number is relatively low, the artist praised prominent women of his period, including A. Toidze, D. Chichinadze, and N. Vachnadze. He presents us women known for their beauty from a unique perspective. He did not let himself be carried away by the representation of the model's exquisite attractiveness, seeking instead to express the inner sentiments of the chosen ladies.

Nikoloz Kandelaki (1889-1970). “Portrait of Vakhtang Beridze”. 32x27x25 cm. Tinted plaster. 1934. Sculptor’s studio

Nikoloz Kandelaki (1889-1970) sculpting a bust of Aleksandra (Shura) Toidze. N.Kandelaki sits in the middle, the first from the right A.Toidze, Georgian Academy of Arts, 1937

In this sense, the image of Nato Vachnadze is particularly fascinating, as it shows a depressed face worn out by life. The delicate approach of the sculpture allows the artist to gently bend the head and use heavy eyelashes to portray the face of a lady lost in thought. It is intriguing that Nato Vachnadze did not have time to sit as a model: she left for Moscow, and never returned. This melancholic work seems to be filled with foreboding.

Nikoloz Kandelaki (1889-1970). “Portrait of Nato Vachnadze”. 78x27x31 cm. Tinted plaster. 1952. Sculptor’s studio

Nikoloz Kandelaki (1889-1970). “Portrait of the sculptor’s spouse – Evgenya Zhukovskaya-Kandelaki”. 78x60x38cm. Tinted plaster. 1952-1953. Sculptor’s studio

Nikoloz Kandelaki took part in various contests for monuments, most of which were not realized. In 1968, in Tsulukidze (Ozurgeti), Kandelaki’s standing monument to P. Tsulukidze was constructed as a symbol of the political views of the new era. Figures of laborers at work are depicted in a low scene. The figures and tools of labor are distributed across the field in a rhythmic manner, in a composition characterized by a pointed laconic and schematic appearance. This approach is not found in Kandelaki's subsequent works, nor is such a style seen among his next generation of students.

Nikoloz Kandelaki was not only a remarkable portraitist, but also a source of inspiration for future Georgian sculptures. His creative origins led to the foundation of the art of Georgian sculpture from the 1940s to the 1990s. This is no exaggeration: Nikoloz Kandelaki’s influence on the cultural landscape of our nation is truly boundless.